by DonnaGibbs | Jun 27, 2016 | Books and Children

Catherine Keenan, the executive director of the Sydney Story Factory and the 2016 Australian of the year Local Hero, is our guest blogger today. Welcome Cath and congratulations on your well deserved award.

In the nearly four years since the Sydney Story Factory opened in Redfern, we’ve taken over 8,000 enrolments from young people aged 7 to 17. We offer them free creative writing and storytelling programs and they have surprised us with everything from poems about robot birds to ghost stories, a pantomime, food reviews, newspapers and podcasts. You can read some of their wonderful stories here.

Most of these young people are marginalised in some way. Around one quarter of our students are Indigenous and just under half are from non-English speaking backgrounds, particularly refugees and asylum seekers. All our programs – whether they’re a one-off two-hour workshop or a term-long program in a school – end in a publication. This might be an animation recorded on a DVD, or a beautifully illustrated book: either way, it’s something the students can take home and proudly show their family. There is nothing like the smile that spreads across the face of an eight-year-old when they hold that publication in their hands. Especially if that child normally struggles with literacy, as many of our students do.

Cath and William at the Story Factory

The thing that makes our workshops different – and makes writing at the Sydney Story Factory different from writing at school – is that our classes are run with volunteers. We have a fantastic staff of expert writers and teachers, and they plan and lead every workshop. But within each workshop, we may have, say, 20 students and 10 volunteers who work with those students one-on-one to support them as they write. The volunteer’s job is to say to the student: “That’s a great idea! Tell me more.” Writing is hard for everyone, whether you’re 7 or 70, and the volunteer is there to help when the student gets stuck. They ask questions and throw ideas around, and gently get the student going again. The volunteers don’t need to be experts in writing, and they don’t need to be teachers (though some of our best volunteers are retired teachers). They just need to be genuinely interested in the children they’re working with. You cannot over-estimate the power of having an adult, who’s not a family member and not a teacher, genuinely engaged with what a child thinks. You can almost see them stand a little bit taller.

There’s one boy I can think of – let’s call him John – whose mum almost literally dragged him through the door when we opened. He hated writing. He had just graduated from a remedial reading program and he would lie over two stools, facing the other way, yelling out “BORING!”

But our volunteers persevered. They didn’t treat him as a kid who was bad at writing; they were relentlessly curious to find out how he was going to finish his story and what would happen next. And very slowly, despite his best efforts, John’s ideas came. When he threw one out, our volunteer would grab it and say: ‘Yes. And? Then he’d have another idea and they’d run with that too. ‘Yes. And?’ At the end of that first course, which we ran in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art, he’d worked with a small group to produce a short stop-motion animated film which was screened at the MCA for parents and friends who clapped and cheered.

Naturally, John still told us he hated the course. But he came back the next term. And the next. And the next. Nearly four years later he’s still coming. In fact, he’s enrolled in our longest ever course, a year-long program to write a novella of up to 30,000 words. He’s a very different boy from the one who first walked through our door. He’s doing better at school, and he’s far more confident as a person. When younger kids come into the Story Factory, he welcomes them and shows them around. We don’t claim credit for all of that, of course, but some part of it is because he has become something he never thought he would be: a writer.

Back in 2011, it seemed a risky decision to leave my job as a journalist at the Sydney Morning Herald to run the Sydney Story Factory. I would never have done it without the tireless and self-effacing support of my co-founder and Herald colleague, Tim Dick. But every time I see John, every time I see that light go on in a child’s eye when they understand the power and joy of words, I know I made the right decision.

For more information, go to http://www.sydneystoryfactory.org.au/. We’re always looking for more volunteers. If you’d like to volunteer, please go to http://www.sydneystoryfactory.org.au/about-volunteering/.

by DonnaGibbs | Jun 14, 2016 | Books and Children

Children’s learning patterns can seem quite mysterious to an adult. The meanings they take from stories, for example, can be different from the meanings we think they take. In an earlier post I described how children need quite some time to work out what is real and what isn’t; and to come to understand the conventions of form and illustration in picture books – all processes which affect how they construct meaning.

Here are some further things to note:

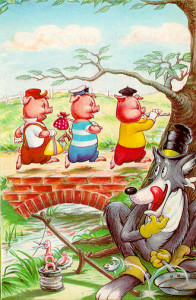

A child’s logic may not seem logical to an adult. For example: A child might ask the following slightly off-track questions during a reading of The Three Little Pigs:

The Three Little Pigs

Why don’t animals eat themselves?

Why don’t wolves blow people’s houses down?

Do pigs wear hats?

Can pigs walk?

The adult sees these questions as irrelevant to the story being read. But the child has to work through many different connections between ideas and how things work in the world before they come to a similar kind of understanding. Their ‘own’ logic is very precious because it is based on seeing the world through new eyes.

What should you do? Should you interrupt your reading so that the thread of the story is lost and try to answer the questions asked as best you can? I think so. If the child’s mind is actively seeking answers then they really need to know what those answers are.

Of course, some children get so caught up with the questions that you never get back to the story. Maybe if this happens you can suggest you have a turn of just listening to the story. But on the whole questions shouldn’t be discouraged – it means the child is learning to think independently.

Children do not have an automatic understanding of idioms, homonyms and word play. Language has many encoded mysteries which adults understand without consciously thinking about them.

For example, a simple word can cause confusion to a child because it has more than one meaning. I recall the word ‘feet’ causing this problem for my daughter when we were reading Winnie-the-Pooh: ‘Oh, help!’ said Pooh, as he dropped ten feet to the branch below him.’

From Winnie-the-Pooh

But in the picture, as Juliet pointed out, Pooh only drops two feet, not ten! She was convinced the author had got it wrong. This kind of confusion is also caused with idioms.

What should you do? It is probably better to talk about these concepts outside of reading time. You could play word games to help this kind of understanding. Then when they do cause confusion in a reading it will be easier to explain what is meant.

Progress in a child’s learning is not continuously forward and may seem to get ‘stuck’ at times. A common learning pattern for a child is to take a step forward, then a step backward, pause there for a time, then move forward again.

Sometimes, a story a child seemed to understand suddenly raises questions from them suggesting they’ve missed the point entirely. There can be many reasons for this but one is that they become temporarily obsessed with something – not necessarily for reasons we understand. Subjects that regularly come under children’s scrutiny in this way include hands; feet; fathers; mothers; who/what looks after who/what; stealing; eating animals; death; and what’s real or pretend. A child will endlessly test out what can be known about their current fascination – they relate it to everything else – both successfully and unsuccessfully, they imitate it, and they see connections that may or may not be there.

What should you do? Understanding that there are common, seemingly irregular, learning patterns that most children work through means there’s no need to feel anxious when a child seems to ‘go backwards’. It is a part of their learning even though it looks as if it’s the opposite!

Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present

Children build on what they know of the world by relating it to their books and their books gain in meanings as they learn more about the world.

This is a reciprocal process which reinforces understanding of a whole range of things. In other words, the books you read to children aren’t only offering them the pleasure of story and enrichment for the imagination. They also help build and consolidate ways of understanding and knowing.

What should you do? You can look out for books that might be helpful for situations relevant to your child. There is almost certainly a book that explores every new situation a child will face such as their ‘first time’ experiences – the dentist, the doctor, kindergarten, school – the death of a pet, the birth of a baby brother or sister and so on. It is best though to try to choose well written books that achieve their purpose in imaginative ways as books of this kind can be of poor quality. Do you have any recommendations?

Recent Comments