by DonnaGibbs | May 11, 2016 | Books and Children

My Kindy group is enjoying Aaron Blabey’s books at the moment. Have you tried any of them? You can read about him here.

He both writes and illustrates his books and, while they may be something of an acquired taste, they are wonderfully unusual.

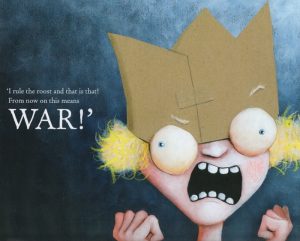

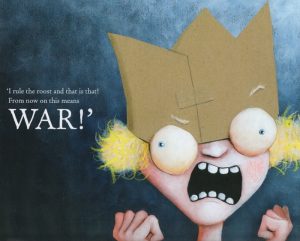

You could try The Brothers Quibble: It begins:

Spalding Quibble ruled the roost.

He shared it with no other.

But then his parents introduced

a brand new baby brother.

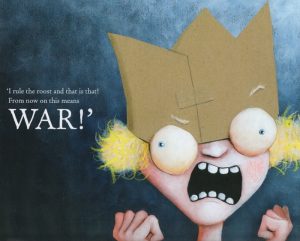

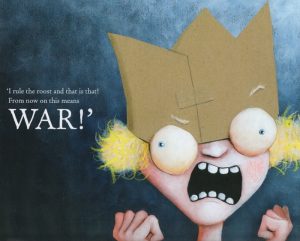

Or you could try Stanley Paste. This is about a boy, Stanley Paste,

Or you could try Stanley Paste. This is about a boy, Stanley Paste,

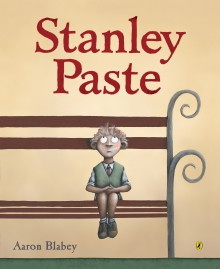

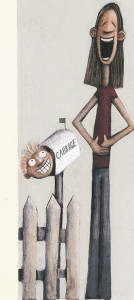

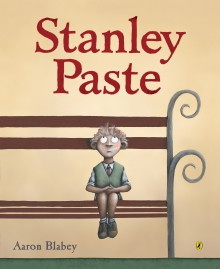

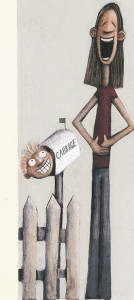

Stanley in the letter box

who hates being small and a girl, Eleanor Cabbage, who hates being tall.

There is a small boy in my class whose laughter, when we come to the

illustration of Stanley in the letterbox, is so infectious that I can’t resist

reading the book just to hear him laugh.

I’d love to hear if you’ve tried any of the Blabey books with young children

and how they respond to them. Are there any authors you’d like to recommend?

by DonnaGibbs | Apr 30, 2016 | Books and Children

Websites for you to browse

Here’s an outline of a few useful sites to help you find advice about children, reading and books on the web. Most sites have some commercial base so you need to read with discrimination – but then that is true of anything you read, especially on the web!

Do you have any sites you’d like to recommend? Please add them to the comment box for others to see.

Purpose: Goodreads was started ‘to help people find and share books they love…’. Amazon purchased it in 2013 presumably to encourage people to buy more books.

Organisation is in genres. Search for lists of books others recommend in any category. Or click on the genres below to see what is currently available:

Sample articles. Click on these titles to see what’s on offer.

Best Graphic Novels for Children

Best Kick-Ass Female Characters From YA and Children’s Fantasy and Science Fiction

Best Children’s Books

The Must-Have Series for Children Ages 6 to 12

Purpose: Aim is to help parents grow life long readers. Created to promote books and reading by Penguin/Random House. Note Amrerican bias.

Organisation is in ages and stages. Click here to see what is currently available:

Sample articles: Click on these titles to see what’s on offer.

Purpose: Pinterest is a visual bookmarking tool that helps you discover and save creative ideas. You can save anything you find around the web to a board you set up for yourself or you can look to see what other people have collected on topics of your choice. I looked at Children and Books here but most topics have a swag of suggestions.

Samples of topics/subjects include:

Children’s Book Council of Australia

Purpose: Established in 1945, the Children’s Book Council of Australia (CBCA) is a not-for-profit, volunteer run organisation which aims to engage the community with literature for young Australians. The CBCA presents annual awards to books of literary merit, for outstanding contribution to Australian children’s literature.

Organisation: Reports lists of notables, short lists and winners of awards by year. Publishes Reading Time online which presents news and reviews of children’s books.

Sample articles:

The benefits of reading aloud to young people

Simon Thorne and the wolf’s den

by DonnaGibbs | Apr 6, 2016 | Books and Children

Get children their own library card

Start the practice of visiting the library at a very young age. Let them choose their own books – a bit of subtle guidance and even sleight of hand may be needed, but children love to choose things for themselves.

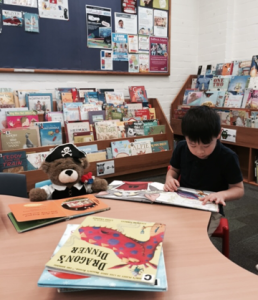

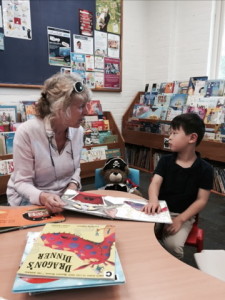

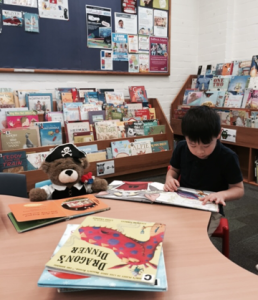

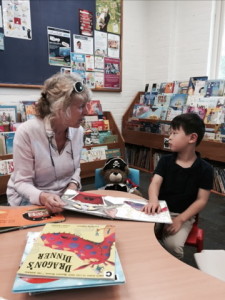

Cooper reading with Patch

I have two special memories of libraries. I was introduced to the Kew library in Victoria when I was 8 (way too old). I can still remember how astonished I was to find you could take books home. When I left the library with my books I kept looking back to see if anyone was following me to take them back again.

My other memory is of Juliet, my daughter, lying on the floor of the library and refusing to get up when it was time to leave. ‘Come on, Juliet,’ I said. ‘I can’t,’ she replied. ‘I’m a library book. I’m  waiting for someone to take me out.’

waiting for someone to take me out.’

I am often found in the children’s section of our local libraries looking for books to read to my Kindy group. That is where I met Cooper with his mother, Lyn. Here he is reading a book of his own choice with his bear, Patch, beside him. He was completely absorbed in his task.

These days libraries offer many different free programs and events to inspire children’s love of books. It is worth checking out what is on for children, especially in the holidays. One program some Queensland libraries have been involved with is First Five Forever which is about how important the first five years of a child’s life are in terms of brain development and learning.

Make books for your children.

You can use your computer to make something that will be special just for your child. It can be done quite simply as a power point or pdf, run off and stapled together. That is a method I used for a book I made called ‘The Great Strawberry Mystery’ for my step grandson, Max. We were visiting in KL and at the time he was very fond of strawberries . You can look at the story The Great Strawberry Mystery.

The Great Strawberry Mystery

Another approach is to purchase a photo book from a commercial firm (eg Snapfish, Photobook) and then paste your text, photos or pictures into it. They will print your book and post it to you. Watch out for their special offers – sometimes they waive postage or offer up to 80% off.

Making up the story need not be difficult. You can take the plot from any story and change the details if you don’t want to invent your own. Or you can write about your child’s daily life and introduce a visit from a storybook character.

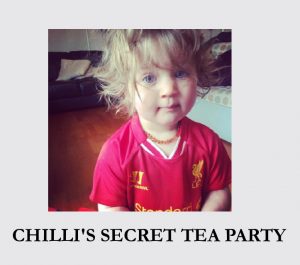

I made a book for my niece, Chilli, called ‘Chilli’s secret tea party’ using Photobook. I knew she loved the Olivia books by Ian Falconer and I had gathered lots of information about her sayings, her friends, what she liked doing and so on. Then I fitted these details into a story that showed Chilli having a secret tea party for Olivia. You can watch her listening to the first part of her book right here on this Facebook video.

It was great fun for me to make and you can see Chilli was very involved right from the start. Her mum says it is a favourite. And it will be interesting for her to look back on when she is older.

Make books with your children.

This can work well with most ages. It is often good to start with something a child draws. Talk about the drawing together. That is how The Rainbow Dragon and The Rainbow Dragon’s Revenge began. My grandson, Oliver, drew a beautiful coloured dragon and it was our talking about his dragon that got us started. Oliver and James, his brother, were soon involved in telling me about its adventures. This gave me a plot to work with (a bit weird and wonderful) and I wrote the stories while the children added illustrations. I made two books with my grandsons in this way. I recently put them on Create Space and made them available online (see my website).

Look out for books about things that chime with your child’s current interests.

As children develop, they move through many different experiences, passions and stages. Tapping into what a child is experiencing at a particular moment and finding books that explore similar things is a great way to capture a child’s interest. An example that brought me a lot of pleasure recently was sparked by a poem in my book, ‘I Like Poems’. Molly had spent many years of her young life wanting a dog and then she finally got one. When she was reading my poetry book, given to her by her grandparents, the poem ‘If…’ about not having a dog really struck a chord. She wrote a poem in response to show what it meant to her to own a dog, a poem full of feeling and empathy.

If . . .

If I had a dog

I’d feed it every day.

I’d brush its coat,

I’d check for fleas,

We’d walk and run and play.

If I had a dog

I’d sneak it in at night.

I’d pat my bed,

I’d make a space,

We’d sleep till it was light.

If I had a

I’d train it to obey.

I’d give commands,

I’d give rewards,

‘twould do just what I say.

If I had a dog

I know that in the end

We’d be a team,

We’d be best friends.

Till then – I’ll just pretend.

Molly wrote a wonderful poem in response.

Now . . .

Now I have a dog

His name is Harvey bear

He’s black and white

And very cute

Of him I take good care

Now I have a dog

He can dance and run and play

He licks and barks

He sneaks our food

He loves us everyday

Now I have a dog

He often goes to sleep

He lies on my bed

He sleeps on my couch

Maybe he’s counting sheep

Now I have a dog

His name is Harvey bear

He’ll be my friend

Until they end

We’ll always be a pair

By Molly

Molly’s Harvey Bear

Finally If I can be of any help with your own book-making experiments please email me. I am far from expert with any of these things but I am willing to help if I can.

by DonnaGibbs | Mar 17, 2016 | Books and Children

Young children take time to learn whether things are living or non-living, real or pretend. In their world these categories are not yet well defined. It may make for a world that has more exciting, even magical, possibilities but it may also at times be more bewildering, frightening or threatening.

Adults bring to picture books a well-defined set of understandings about how the world works and how the picture book format interprets experience. It takes considerable time for a young child to acquire a similar kind of understanding and ‘background’ knowledge.

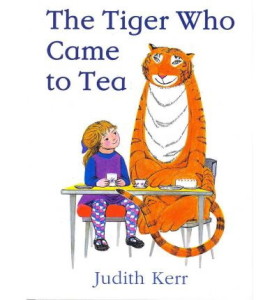

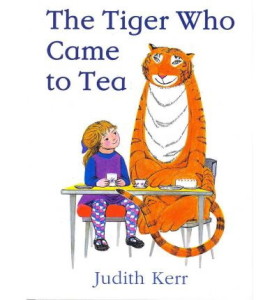

They may know, for example, at one level that illustrations aren’t real and that they represent things from the real world. But at another level they believe that the characters or animals in their books are real. ‘Where did the tiger go?’ asked a boy at kindergarten yesterday when I had just finished reading The Tiger who came to tea. For him, that tiger was out there somewhere. He might even come to visit his house and stay for tea!

Young children take time to learn how illustrations represent things. Adults understand that a partial illustration or a side view of, say, a fox represents the whole fox. A child on the other hand will ask ‘Where are his other two legs?’ and turn over the page to see if they are on the back of it. When I was reading Noah’s Ark to my daughter, Juliet, many moons ago, she thought the ostrich, who had only one leg showing, ‘must have his other leg at the animal hospital where they fix legs.’ (I only remember this because I kept a diary of our reading when she was three until she turned five.)

‘What’s the matter with Mary Jane?’ from When we were very young by A.A. Milne. Illustration by Ernest H. Shepard

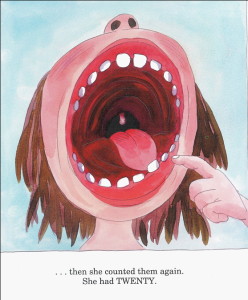

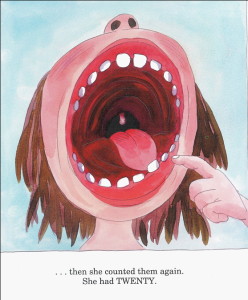

From I want my tooth! by Tony Ross (A Little Princess Story)

A child’s background and experience can also colour what they see. As a child I was sure that the thing buzzing around Mary Jane’s head was a fly. As an adult I came to realise it was her shoe she’d kicked off because of that rice pudding. This had never occurred to me as a way of venting my frustrations as a child though I am sure I hated rice pudding just as much as Mary Jane.

Size in illustrations is another convention that needs to be understood. Children do not always recognise the rules of perspective, for example. A figure who is small and a long way off may, in fact, be larger than a figure in the foreground. Very confusing if you don’t know the rules.

From The Helen Oxenbury Nursery Rhyme Book. Er . . is that a real horse?

Size is also used for other purposes than representing reality in children’s books. It can draw attention to something as does this wonderful illustration from I want my tooth by Tony Ross. The Little Princess’s mouth and teeth fill the left hand page yet on the facing page her mouth is the same size as everyone else’s. Size exaggerates, distorts, creates fear – it achieves all sorts of things in picture books. Children respond enthusiastically to these techniques without necessarily understanding them.

Young children will not yet know the meaning of many of the words they hear when listening to a story. They may not understand enough to ask for meanings and it may take time for them to recognise what they don’t know and to learn how to ask. This plays some part in why children love to hear the same story over and over. As you know, young children love repetition, rather more than you do! ‘Repetition Rules’ has more to say on this subject.

Knowing that each part of a story contributes to the whole takes time for a child to appreciate. It isn’t immediately obvious to a child that a story has a beginning,a middle and an end. After all, many of their earliest board books are not structured in this way. For reasons of their own, young children may be more impressed with parts of a story or its pictures than with the story as a whole.

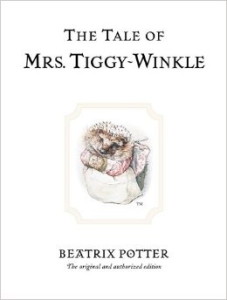

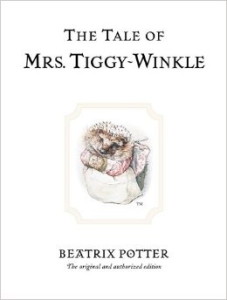

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children need time to come to grasp the concepts that shape what we hear and see which we take for granted. They will find their own way, and they don’t need to be hurried, but it does help if we can support them along the way by understanding the complex processes involved.

Do these observations chime with any you have made? Comments most welcome.

Future blog topics: Please send any topics you’d like me to talk about either by posting here or by emailing me your thoughts (gibbs.donna@gmail.com/).

by DonnaGibbs | Mar 9, 2016 | Books and Children

Does it matter which version of a classic story you read to your child? Well – yes and no. You can be fairly sure the time tested magic of these tales, as long as age appropriate, will probably spread their enchantment, whichever the version. But there is more to it.

What started me thinking about this was some additional suggestions for popular books for two and a half year olds that came my way after my last post:

The Gingerbread Man

The Three Billy Goats Gruff

The Three Bears

Little Red Riding Hood

These classics, mostly originating as oral tales, come in many written versions. Different story tellers have told and illustrated the tales in different ways over time. Did you know that Goldilocks, for example, was originally a fox, not a girl, in earlier versions of the story? If you want to learn more about changes in these tales, dip into Iona and Peter Opie’s book, The Classic Fairy Tales. It is a fascinating study.

Dore’s illustration of Red Riding Hood, 1872, from the Opie’s Classic Fairy Tales.

Modern retellings of classic tales with a wide range of illustration styles continue to be produced. Call up Google images and type in a title or a character’s name to see what I mean.

Each version of a classic tale, through its choice of words and style of illustration, tells a different story. Some wordings are so beautifully crafted that you find yourself slipping into the forest with the characters, pausing there wide-eyed in delicious fear, making judgements and weighing up the possibilities. Other writers tell their stories more prosaically leaving a reader’s senses and empathies unengaged.

It is not only the words of the stories that carry values, create a moral world and play with stereotypes. For example, if Goldilocks lives up to her name and is pictured as the traditionally beautiful golden long-haired girl (as she is in the illustration below), then she is somehow made into a virtuous heroine with right on her side – even though she is the one to break into the three bear’s cottage and steal their food!

From Raphael Tuck’s ‘Combined Expanding Toy and Painting book series.’ c 1900

If, on the other hand, she is pictured as a dumpy, curly haired miss, with very poor dress sense, the story changes. The bears wouldn’t stand a chance against her! You can imagine this Goldilocks giving the door a good bang or even a kick, and shouting loudly, ‘Is anyone there? I’m hungry.’ Same story, but very different messages being sent through the illustrations.

So, is it ok to stick with a Disney version of one of these famous tales. Probably not. Children deserve to hear well written, well illustrated, age appropriate versions of classic tales. I wouldn’t avoid a Disney version but reading different versions at different times seems to me a good option. After all, children must to learn to discriminate for themselves. And it’s good for children to learn there are different ways of telling – a vital understanding that takes time to absorb and a concept on which many other concepts depend.

In my experience, children listening to classic tales become quite still and quiet. There is a special quality to their silence. You can actually see the magic of the story take hold. Have you found this? Are there any versions of classic tales you would recommend?

A different kind of Goldilocks.

* * * * * * * * *

Or you could try Stanley Paste. This is about a boy, Stanley Paste,

Or you could try Stanley Paste. This is about a boy, Stanley Paste,

waiting for someone to take me out.’

waiting for someone to take me out.’

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Children also notice things in a picture book that an adult may not notice or find unimportant. They are attuned to illustrations in ways it may be hard for us to anticipate. I recall, for example, my daughter’s obsession with the fate of a bird that had nothing at all to do with the plot of the book I was reading her, Mrs Tiggiwinkle by Beatrix Potter. At each new page she would ask ‘Where is that bird ? What is he doing now?’ It is disconcerting for the reader but it helps if you understand that a child’s logic is often quite quite different from your own.

Recent Comments